Prospect and Refuge, Hunters and Prey

In the patch of woods just outside the school office, three boys sneak by. Two more lurk deeper in the trees. Suddenly, they’re sprinting across the school grounds. Two outdoor games have been big on campus lately: “Hunters and Prey” and “Infected.” Both are hide-and-seek variants and can involve anywhere from ten to thirty students at a time. Hallmarks include people flashing past, hiding as long as possible, and shouting from deep in the forest. Games can last for hours.

Crossing from one building to the other yesterday, taking a few minutes to deeply notice the players, I again asked the question we ask so many times : what’s going on here? Obviously, the players are breathing fresh air, exercising, and developing relationships, all hallmarks of outdoor play. Furthermore, the open-ended quality of the games fosters critical and strategic thinking in the players. But what about these particular games makes them so compelling?

Intense games of hiding and seeking seem to reinforce biological drives and instincts. Quoting from landscape theorist Jay Appleton’s Prospect-Refuge theory,

“at both human and sub-human level the ability to see and the ability to hide are both important in calculating a creature’s survival prospects . . . . Where he has an unimpeded opportunity to see we can call it a prospect. Where he has an opportunity to hide, a refuge. . . . To this . . . aesthetic hypothesis we can apply the name prospect-refuge theory.”

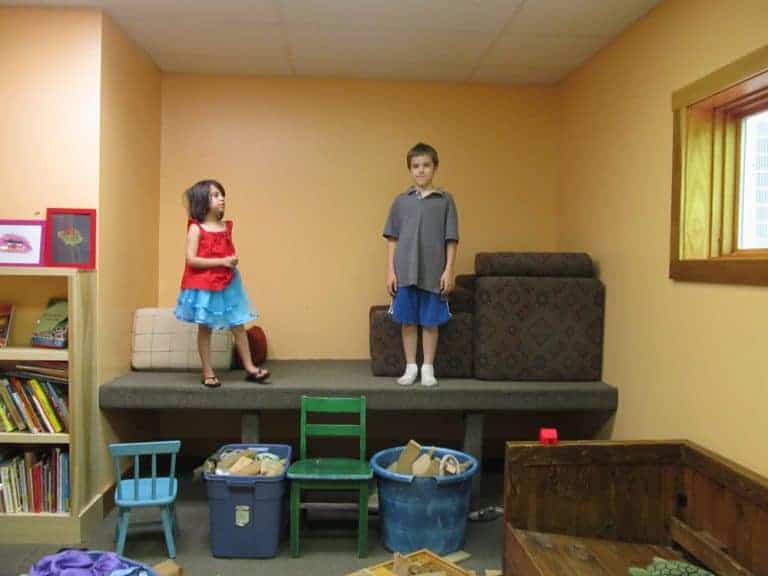

We are hard-wired, then, both to take refuge and to seek higher ground. For millions of years on the savanna, or in the woodlands, humans needed both prospect and refuge to literally survive. Here in the Mid-Atlantic, wolves are long gone, as are saber-toothed tigers. Most students get their food from supermarkets. Still, they satisfy basic drives when they play their games. Although whether or not they will survive may not be at stake, whether or not they will thrive surely is. Brains and bodies anticipate the need to find prospect and refuge, to seek and to hide. At Fairhaven, the students fulfill this need.

Our working thesis is that free range young people develop best. Playing Hunters and Prey, from a point of prospect, they are learning how to take stock of a situation and they then experience the good (or bad) things that this assessment brings. They are also learning how to hide, or more broadly put, to take refuge. Refining these individual traits in the social matrix of a game only intensifies their value. Given the stakes and the outcomes, the oft-repeated phrase it’s just a game falls short of the complexity.

Later in the day, two students relax from the prospect of the wrought iron rockers on the porch, the highest ground at Fairhaven. Noticeably pleased to be blending in by talking with me, they tell me casually that they’re playing, that they’re part of the game swirling below. Nevertheless, some aspect of them stands ready, at a moment’s notice, to spring from their spots at the merest whiff of an approaching hunter.

Mark McCaig

January, 2009